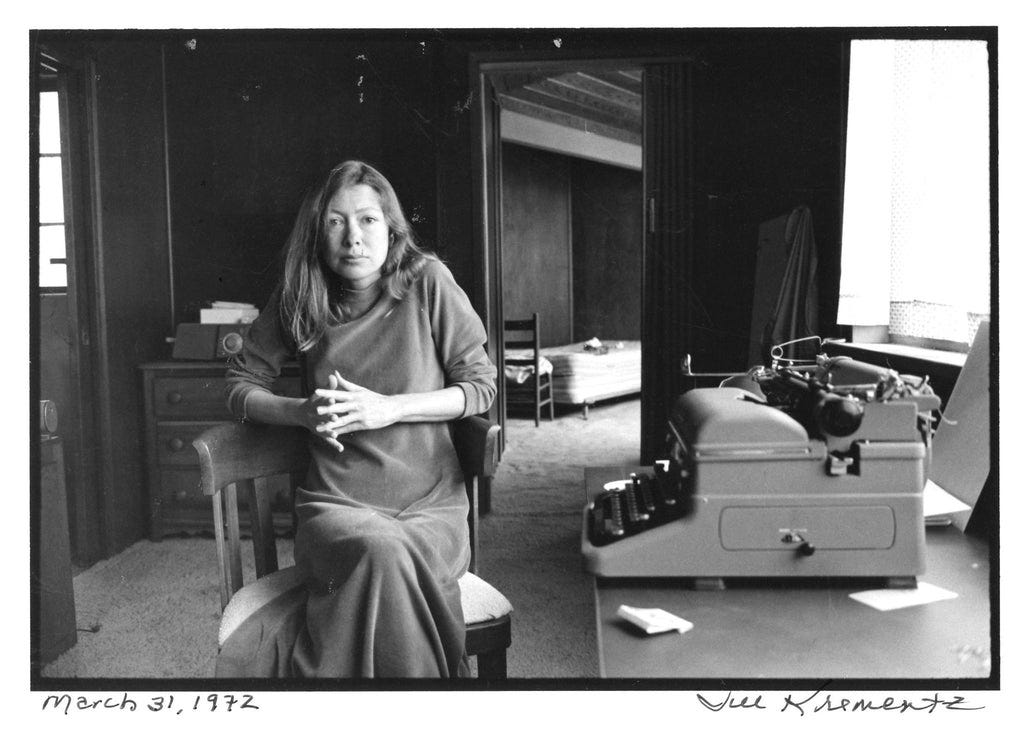

In our chaotic world few writers have ever captured its complexities with more clarity than Joan Didion. Never interested in easy answers or neat conclusions, she wrote to make sense of the mess. She was skeptical but never cynical, sharp but never cruel. Whether writing about politics or grief, she made the familiar feel strange and the strange feel familiar. At her core, she had an unmatched ability to distil big, sprawling ideas into precise, elegant, quietly shattering prose.

I know we’re all busy, but if you can spare a few moments, I highly recommend (re)immersing yourself in her world and seeing the world through her words. Her observations and ideas are more relevant than ever. And, if you only have time for a couple of things this week, I’d recommend the links on Slouching Towards Bethlehem and A Year of Magical Thinking.

1. This week’s post was prompted by an article in last week’s New York Times about an unexpected, new book coming out in April: Notes to John.

“Shortly after Didion’s death in 2021, her three literary trustees found the diary while going through her papers in her Manhattan apartment. There were 46 entries stashed in an unlabelled folder and addressed to her husband, John Gregory Dunne. Didion left no instructions about how to handle the journal after her death, and no one in her professional orbit knew of its existence.

Didion’s journal was crafted with the singular intelligence, precision and elegance that characterise all of her writing. It is an unprecedentedly intimate account that reveals sides of her that were unknown, but the voice is unmistakably hers - questioning, courageous, and clear in the face of a wrenchingly painful journey.” Pre-order Notes to John here.

2. In her 1976 article in the New York Times, “Why I Write” she explains:

The opening paragraph from the piece:

“In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions - with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating - but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.”

3. I reread Slouching Towards Bethlehem over the Christmas break. It’s her at her sharpest, observing the unravelling of 1960s America and capturing the disillusionment beneath the flower-child idealism…

“The center was not holding. It was a country of bankruptcy notices and public-auction announcements and commonplace reports of casual killings and misplaced children and abandoned homes and vandals who misspelled even the four-letter words they scrawled.”

“Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and the future as snakes shed their skins, children who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together.”

…combined with enduring perspectives on self-compassion and awareness:

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.”

4. In Political Fictions (2001), and long before the rise of "fake news" discourse, she was already questioning the way power distorts truth, not through outright lies but through the subtle, deliberate framing of reality.

“The genuflection toward ‘fairness’ was in fact a genuflection in the direction of the already successful, the people who had already made it, the people who had the power.”

She understood that American politics had become more about storytelling than governance. She wasn’t just skeptical of politicians, she was skeptical of the journalists who allowed themselves to be manipulated by spin, reducing democracy to a carefully managed illusion.

[As an aside, Ian Dunt last week wrote a powerful piece on exactly this subject called “Journalism is collapsing in the middle of the information war” which starts with a cracking opening line: “This is how the media collapsed: economically, then editorially, then politically.” Thoroughly recommend.]

5. I’m fascinated by the stories and details surrounding her writing and life. For example, as a young writer, Joan Didion engaged in a meticulous and almost obsessive exercise: she retyped entire passages of Ernest Hemingway’s novels to dissect and internalise his sentence structure, rhythm, and economy of language. Didion later explained this practice in a 1978 interview with The Paris Review, describing how typing out Hemingway’s prose allowed her to absorb the mechanics of his style in a way that simply reading couldn’t.

“When I was fifteen or sixteen I would type out his stories to learn how the sentences worked. I taught myself to type at the same time. A few years ago when I was teaching a course at Berkeley I reread A Farewell to Arms and fell right back into those sentences. I mean they're perfect sentences. Very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite, no sinkholes.”

6. And this: in The White Album, she explains her habit of keeping an overnight bag packed, describing it with her characteristic precision:

“I had by all accounts a ‘cool’ life, the kind of life in which one is on call to fly to Bogota at midnight. In fact, I did make an abrupt trip to Bogotá during this period, and when I went to get my luggage, I found that I had in my bag two skirts, two jerseys, one leotard, a bottle of bourbon, and a typewriter. This was perhaps an adequate representation of my state of mind at the time.”

7. Her marriage to John Gregory Dunne was equally a literary partnership. It was intimate and sharp, marked by unwavering dedication to the craft and a brutal honesty in their critiques of each other’s work. Didion once described their working relationship as a constant back-and-forth, filled with arguments and revisions. “We would sit in the same room and yell at each other all day,” she recalled in a 2005 New York Times interview. Related to this, one of my favourite quotes of hers, a line that never fails to make me smile: “I did not always think he was right nor did he always think I was right but we were each the person the other trusted.”

8. Didion’s final two decades were marked by profound loss. On December 30, 2003, Dunne and Didion returned home from visiting their daughter, Quintana, in the hospital where she was in a coma. Dunne suddenly dropped dead from a heart attack. Didion told the story of her year of grief in “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), which won the National Book Award. Just before the book was published, Quintana died.

Grief is the hardest thing to write about. She did it as a reporter. Written with her signature precision and restraint, the book is both deeply personal and universally resonant. It’s a perfect meditation on love, loss and the fragile logic we cling to when the unthinkable happens.

9. Here are the opening lines, followed by a few short quotes from the book: “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

“This is my attempt to make sense of the period that followed, weeks and then months that cut loose any fixed idea I ever had about death, about illness, about probability and luck, about marriage and children and memory, about the shallowness of sanity, about life itself.”

“People who have recently lost someone have a certain look, recognisable maybe only to those who have seen that look on their own faces. I have noticed it on my face and I notice it now on others. The look is one of extreme vulnerability, nakedness, openness. It is the look of someone who walks from the ophthalmologist's office into the bright daylight with dilated eyes, or of someone who wears glasses and is suddenly made to take them off. These people who have lost someone look naked because they think themselves invisible. I myself felt invisible for a period of time, incorporeal. I seemed to have crossed one of those legendary rivers that divide the living from the dead, entered a place in which I could be seen only by those who were themselves recently bereaved. I understood for the first time the power in the image of the rivers, the Styx, the Lethe, the cloaked ferryman with his pole. I understood for the first time the meaning in the practice of suttee. Widows did not throw themselves on the burning raft out of grief. The burning raft was instead an accurate representation of the place to which their grief (not their families, not the community, not custom, their grief) had taken them.”

“We are not idealised wild things. We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.”

10. Finally, there’s a great Netflix film from 2017 called “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold” a documentary capturing her life, work and unique way of seeing the world. “I’ve always found that if I examine something it’s less scary.”

Have a great weekend, Matt

Quote of the week: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live...We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” Joan Didion, The White Album